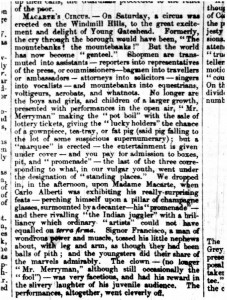

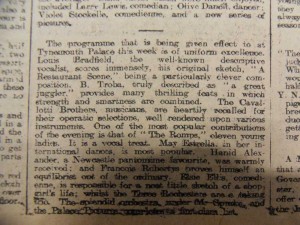

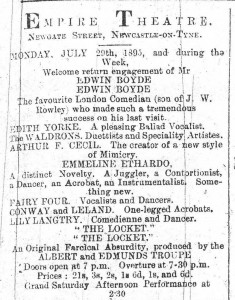

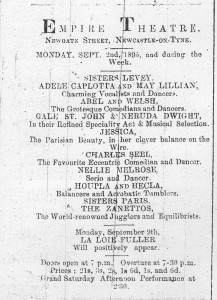

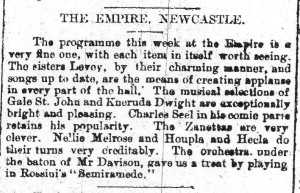

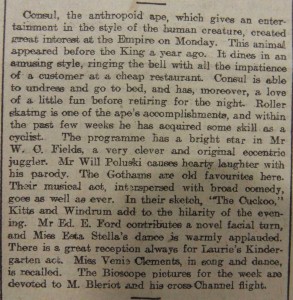

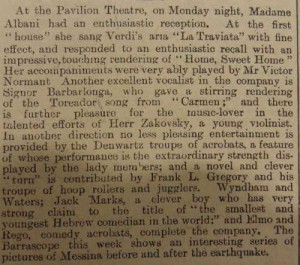

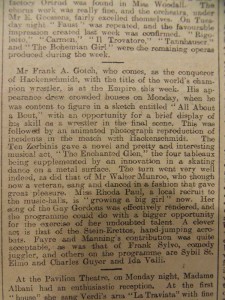

The story of “The Juggler of Notre Dame” has appeared in lots of places over the years. It was origanlly written in French (named Le Jongleur de Notre Dame) by Anatole France in 1892, but it has it roots in a traditional medieval tale. On Saturday 22 April 1893 this translation was published in The Newcastle Weekly Courant:

THE JUGGLER OF NOTRE DAME

In France, during the time of King Louis, there lived a poor juggler named Barnabe, a native of Campeigne, who went from town to town giving exhibitions of strength and skill.

On fair-days he would spread out in the public square a piece of worn-out carpet, and after having collected around him all the children and idlers in the district by a droll discourse, which he has learned from a very old juggler, and of which he never altered a word, he would assume attitudes which were not in the leas natural, and balance a brass plate on his nose. The crowd at first watched with indifference.

But when, after a while, he would stand on his hands, head downward, and throw and catch with his feet copper balls, which flashed and glittered in the sunlight, or when, bending backward until the nape of his neck touched his heels, he would cause his body to assume the shape of a perfect wheel, and juggle with twelve knives in that posture, a murmur of admiration arose in the audience, and small coins rained upon the carpet.

However, like most of those who live by their talents, Barnabe of Campeigne found it hard work to get along. In earning his bread by the sweat of his brow it seemed that he had to bear more than his share of the burdens attached to the sin of Adam, our father. He could not work enough to meet his wants. In order to do himself full justice, he needed, like the trees to put forth flowers and fruit, the warmth of the sun and the bright light of day. In the winter he was a tree denuded of its leaves and all but dead. The frozen ground has harsh and unyielding to his necessity, and, like the grasshopper of which Marie of France speaks, he suffered much from the cold and hunger in the hard season. But his heart was simple, and he bore his ills in patience.

He had never though much about the origin of riches, nor the inequality of human conditions. He firmly trusted that, since this world was bad, the next one must surely be better, and this hop sustained him. He did not imitate those worthless, thieving strollers who have sold their souls to the devil. He never took in vain the name of God: he lived in honesty, and, though he had no wife of his own, he never coveted his neighbour’s.

In truth it cost him more to renounce the ale jug than the ladies, for, without departing from a decent sobriety, he loved to quench his thirst in the heat of the day. He was a worthy, God-fearing man, and most zealous in his worship of the Virgin Mary. He never failed when in a church to kneel before the image of the Mother of God and address to her this prayer:

“Madame, watch over my life until it please God that I should die, and after death vouchsafe that I shall taste the joys of Paradise.”

Now one evening, as he was walking along, bowed and sad, with his copper balls under his arm and his knives rolled up in the old carpet, seeking some barn where he might find supperless rest and shelter, he was a monk coming down the road in the same direction as himself, and he respectfully saluted him, As they walked side buy side, at about the same gait, they soon fell to conversing.

“Friend,” said the month, “how is it that you are thus arrayed all in green – perchance you take part in some mystery?”

“No, indeed my father,” answered Barnabe. “Such as you see me, I am Barnabe, a juggler by calling. The finest calling in the world, if it but enabled one to eat every day.”

“Friend Barnabe,” replied the monk, “look to what you are assaying; there is no finer calling than ours. We are continuously singing the praises of God, the Virgin and the saints, and the monk’s life is one perpetual hymn to the Lord.”

Barnabe replied:

“My father, I confess that I have ignorantly spoken. My profession cannot be compared to yours; and though there may be some slight merit in dancing with a coin balanced on the end of your nose, I confess that it can in no way equal your holy practices. I would like it very well, Father, if I might sing the service every day like you, and especially the service of the most Holy Virgin, whose devout worshipper I am. I would willingly renounce an art by which I am renowned from Soissons to Beaulieu in more than six hundred towns and villages, to embrace the monastic life.”

The monk was touched by the juggler’s simplicity, and as he was not lacking discernment, he recognised in Barnabe one of those righteously inclined men of whom our Lord has said, “Peace be with them on earth!”

“Friend Barnabe, come with me and I will procure your admission to the convent of which I am Prior. He who conducted Mary the Egyptian across the desert has placed me in your path to lead you into the way of salvation.”

It was in this way that Barnabe became a monk. In the convent, where he was received, the good brothers were ardent enough in the worship of the Virgin Mary, and each one employed all the knowledge and skill with which God had endowed him, to do her honour.

The Prior, for his part, wrote books which treated, according to scholastic rules, of the virtues of the Mother of God, and Father Alexander illuminated them with fine miniatures, in which the Queen of Heaven could be seen seated upon Solomon’s throne, with four lions guarding its foot, and seven doves fluttering around her nimbused head to symbolise the seven gifts of the Holt Ghost. She had for companions six golden-haired virgins: Humility, Prudence, Seclusion, Respect, Virginity and Obedience. At her feet were two little naked, white-robed figures, in an attitude of supplication. They were souls imploring, certainly not in vain, her all-powerful intercession for the final grace.

On another page, Father Alexander represented Eve under the eyes of Mary, so that one glance of the observer might embrace both sin and its redemption, the woman crushed to earth and the exalted Virgin.

Father Marbode as also one of Mary’s devoted sons. He was continuously chiselling little images out of stone, so that his hair, beard and eyebrows were white with the dust, and his eyes were all swollen and weary, but he was hale and hearty at a very advanced age – undeniably the Queen of Paradise protected her child’s declining years.

And, besides, they had poets in the convent, who wrote prose and hymns in honour of the most-glorious Virgin Mary, , and they even counted amongst their number a Picardian, who related the miracles of Our Lady in the vulgar tongue and in rhymed verses.

When he saw this rich harvest of works and heard the swelling chorus of praise, Barnabe was sad at heart, and bewailed his ignorance and simplicity. “Alas!” sighed he, as he walked alone in the little shadeless garden of the convent, “how unhappy I am that I cannot, like my brothers, pay worthy homage to the Holt Mother of God, to whom I have dedicated the whole love of my heart. Alas! Alas! I am a rude untutored boor, and I can bring to your service, Holy Virgin, neither edifying sermons not scholarly treatises, nor fine paintings, nor perfectly chiselled images, nor verses counted in feet and walking in step”

After this fashion he moaned and lamented and abandoned himself to the deepest grief. One evening, when the brothers were conversing, for recreation, he heard one of them tell the story of the monk who new no single thing to recite but the Ave Maria. This good man was despised for his ignorance during his lifetime, but in death five roses sprang from his lips, in honour of the five letters of the same name Maria, and thus was his sainthood made manifest.

As he listed to this recital, Barnabe was no more than ever filled with admiration for the Virgin’s goodness, but he was not consoled by the example of this most blessed death, for his heart was full of zeal, and he burned to achieve at once something that was new to the glory of his Lady in Heaven.

He sought long without finding the means to accomplish his end, and day by day he became more afflicted. At last one morning he awoke in joyful mood and ran straightaway to the chapel, where he remained more than an hour alone. He returned there again after the mid-day meal.

And from this time be betook himself every day to the chapel at the hour when it was deserted, and he spent there a great part of the time that the other monks devoted to the practice of their liberal and mechanical arts. Conduct as singular soon aroused the curiosity of his companions, and the questions soon passed around in the community, why Brother Barnabe made such frequent retreats.

The Prior, whose duty it is to acquaint himself with every particular in the conduct of each member of his flock, resolved to watch Barnabe in his seclusion. So one day, when the latter had shut himself up in the chapel, as was his wont, the Prior, accompanied by two of the oldest monks in the convent, came and took his stand at the door and peeped through the cracks at what went on within.

They saw Barnabe, head downward and feet in the air in front of the Holy Virgin’s altar, juggling with six copper balls and twelve knives.

He was performing in hour of the Mother of God the difficult feats which had once won for him the most applause. Not understanding that this simple man was thus giving all his knowledge and talent in loving service to the Virgin, the two old men cried out that sacrilege was being done.

The Prior knew the innocence of Barnabe’s heart, but he believed him to be demented. They all three prepared to remove him in haste from the chapel, when they saw the Holy Virgin descend the altar steps and wipe away with her blue mantle the pearling drops of sweat from the poor juggler’s brow.

The Prior prostrated himself with his face against the stones and recited these words: “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God!”

“Amen!” responded the old men, and they kissed the floor. – From the French of Anatole France.

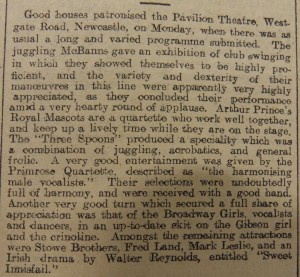

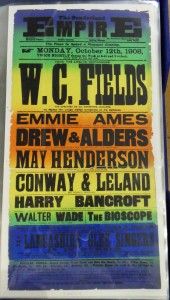

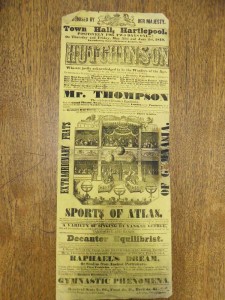

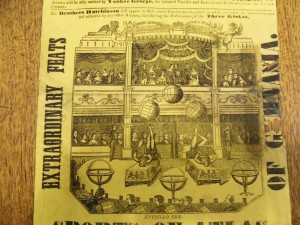

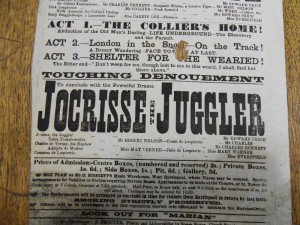

(See the bottom of this article for an image of the original text).